Submitted by William R. “Bill” Beavans; edited and vetted by Cheri Todd Molter

William “Billy” Beavans, a Confederate soldier from Halifax County, N.C., served in Company I of the 1st North Carolina Infantry Regiment and with the 43rd North Carolina Infantry Regiment, Company D. He was wounded at Snicker’s Gap, Virginia, on July 18, 1864 and died of his wounds at Winchester, Virginia, on July 31, 1864. The North Carolina collection at UNC-CH library contains William Beavans’s original diary, dated January 1861 to July 1864, which includes intermittent entries written at home in Halifax County and during the Civil War while campaigning in Virginia with the 1st North Carolina Infantry Regiment in 1861, and with the 43rd North Carolina Infantry Regiment in 1862 through 1864. The diary documents weather, reading, drilling, troop movements, and includes drafts of love letters and poems, remarks about the women Billy courted, and memoranda regarding ordnance, mess accounts, and finances. Also included in the collection is a letter to Maggie Beavans, Billy’s sister, commenting on the conscript law, measles, and camp life.

The following is part of a series “Echoes from the Fort” by the Williamston Enterprise newspaper and was published on October 15, 1998 and written by historian Elizabeth Whitley Roberson to commemorate the 13th Annual Living History Weekend, November 7-8 at Fort Branch near Hamilton.

The following is part of a series “Echoes from the Fort” by the Williamston Enterprise newspaper and was published on October 15, 1998 and written by historian Elizabeth Whitley Roberson to commemorate the 13th Annual Living History Weekend, November 7-8 at Fort Branch near Hamilton.

“Smiling Billy Beavans”

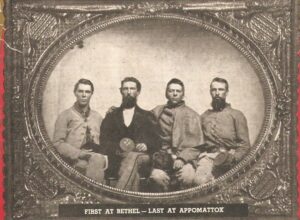

In 1861, at the outbreak of the [Civil War], a family group of six young men from Halifax County answered the call to duty but only two of them would live to surrender at Appomattox four years later. They were brothers Cary and [John Simmons] Sim Whitaker, their cousins Billy and Johnny Beavans, another cousin and uncle, George [Whitaker] Wills, and his manservant Washington Wills better known as “Wash”. The Whitaker boys lived at Strawberry Hill near Enfield, the Beavans at nearby Centreville [Centerville] Plantation and George and Wash at Brinkleyville. Today’s article will be about young Billy Beavans.

“Smiling” Billy Beavans, as he was called, was only 21 years old when he marched away with the Enfield Blues on April 26, 1861. He had been working for some time as a clerk in a store in Hamilton, NC, when he received word that his friends and relatives were joining the army and he quickly gathered his belongings and headed home. He was so disappointed when he arrived home to find that the regiment left without him, however it didn’t take him long to catch up with them in Goldsboro.

The boys spent the night in a hotel in Goldsboro. The next morning, they attended services at the Methodist Church and afterwards boarded a train for Raleigh. Upon their arrival in Raleigh, they were directed to Camp Ellis, which had previously only served as the state fair grounds. Billy Beavans wrote that evening that “all the boys were well in camp.”

Their regiment was call “The Enfield Blues” and was organized just after John Brown’s raid on Harper’s Ferry in 1859. …They continued to do their close-order drills and the various formations they had learned, so when called to active duty in the spring of 1861, they were ready to go. The troops trained in Raleigh for several weeks and finally received orders to board a train for Richmond on May 21st. Upon their arrival there, the local citizens gave them a hearty welcome, tossing flowers and snacks to the hungry men. A few days later they were on their way to Yorktown where Federal troops had begun to gather. Billy had a premonition of unpleasantness as they formed columns and headed southwest in a heavy cold rain. Their destination was the Big Bethel Church, and it would be here that the Confederacy’s baptism of fire would begin. It would be in this battle the first North Carolinian to die would be that of Henry Lawson Wyatt of Martin County.

After this battle in which he saw so many comrades fall, “Smiling” Billy was now just plain Billy. The realization that war was real and that the bullets were real sobered all the young men of the regiment, and when their six-month enlistment was up, they returned home to Enfield. For several months they rejoined old friends, going to parties and trying to forget the scenes of war, but as news began to come in about the fall of Roanoke Island and the fall of Ft. Henry on the Tennessee River, duty began pushing them back into service. [On February 25, 1862, Billy reenlisted as First Sergeant in the Confederate Army.] On March 7, 1862, [he] boarded the train for Raleigh where Cary Whitaker was gathering his troops.

Upon arrival in camp, Billy and his cousin George [Whitaker Wills] were sworn into the 43rd North Carolina Regiment and [each] given a dress uniform, a suit of fatigues, an overcoat, two shirts, two pairs of drawers and two pairs of shoes. [On April 23, 1862, Billy was promoted to Third Lieutenant.] For several months they camped around Kinston and Goldsboro guarding the area from federal attacks from the coast.

In April, they marched to Washington, NC to help guard the town against Yankee gunboats that were shelling the town. In May they turned their sights toward Virginia where they became part of the Army of Northern Virginia. Their first assignment there was to head toward the Shenandoah Valley. By June [1863] they were headed toward a little town in Pennsylvania called Gettysburg. They served nobly there with all of Billy’s family surviving, even though they were in the thick of battle. [Billy was promoted to Second Lieutenant on July 26, 1863.]

The following April they were back in North Carolina where they participated in the Battle of Plymouth, after which they were sent back to Virginia to participate in the Battle of the Wilderness, Drewry’s Bluff, the Bloody Angle and Cold Harbor. In July [1864] …the Confederate forces were lined up at Snicker’s [Gap] facing a strong concentration of federal troops. Billy, who was a cannoneer, was directing the firing of his cannon when he felt a smashing blow against his right leg. He fell to the ground, stunned and helpless. His commanding officer, his cousin George Whitaker Wills, heard his name called out from the darkness and, upon searching the area, found Billy lying on the ground trying gamely to smile his usual smile.

George saw immediately the seriousness of the wound [and knew] that the leg would probably have to be amputated. George had Billy put on a stretcher and carried him to the field hospital. Billy kept drifting into unconsciousness but the men carrying him heard him softly repeating the comforting words of the 23rd Psalm. The next morning the surgeon made the decision to amputate Billy’s leg and without anesthesia. Billy endured the pain with little but a stiff drink of brandy. In spite of it all, however, he maintained his good humor and flashed his usual good smile as he was lifted into the ambulance bound for Winchester.

Billy’s smile, as usual, charmed the girls who came to tend the sick there in the hospital. One in particular was Miss Kate Shepherd who came every day to sit beside his bed. He seemed to be recovering at first but in a very short while he began to weaken. Realizing he was not going to survive, he talked of impending death to Kate. He stated that he would like to live to see his parents again, but he knew now he would not see them again on this earth.

Kate stayed with him all that day as he drifted in and out in a delirious state, mumbling at times about home, the parties he loved so much, the pretty girls he had charmed, the singing of his church choir, and the sermons he had heard his uncle preach. At 5 o’clock on July [31], 1864, 24-year-old Billy Beavans was pronounced dead. In a letter Kate wrote to Billy’s parents, she quoted his last words: “Tell my parents I have but one regret in leaving this world and that is leaving them behind.”

Billy’s cousin Jack had been with him at the last and he hurriedly scoured the town of Winchester for a coffin to put him in. A local citizen offered a place in his private graveyard where Billy’s coffin could be buried until it could be shipped home, but Kate Shepherd insisted that it be taken and buried in her own family plot in Winchester Cemetery. His body was never moved back to Halifax County but rests in the North Carolina section in Mt. Hebron Cemetery in Winchester.

An interesting footnote to “Smiling” Billy’s story took place two years ago when Don Torrence, Jr., a local re-enactor with the 1st NC Regiment, was on his way to Winchester for a battle re-enactment. He stopped by the cemetery at Whitaker’s Chapel church where all of the Billy’s family is buried and where a memorial marker stands in memory of Billy. He scooped up a small can of soil there and carried it with him to Winchester. He found Billy’s grave in Winchester and scattered the “dirt from home” over his grave, hoping in some way to assuage the pain of lying so far from home.

Note: [On September 19, 1864,] George [Whitaker] Wills was killed at Winchester. His body was left on the field of battle, which was captured by the enemy, and…was never recovered nor has his grave ever found. Billy’s brother Johnny was wounded [on May 30, 1864 at Bethesda Church, VA] and sent back home. [However, he returned in November of the same year and served through the remainder of the war. According to his military records, he surrendered with the rest of his regiment on April 9, 1865 at Appomattox Court House.] Cary Whitaker had [wounds on both hands], which turned gangrenous, and he died [April 19, 1865 at the hospital in Danville, VA]. He is buried at Whitaker’s Chapel. The other survivors were [John Simmons] Sim Whitaker and the…servant, “Wash” Wills.