Researched and written by Cheri Todd Molter and Kobe M. Brown

Jonas Elias Pope was born on February 1, 1827, at Rich Square in Northampton County, NC. His father was Elias Pope, a free person of color with a mixed-race heritage who owned land and supported a sizable family. According to census records, Jonas Elias Pope was, like his father, a free person of color, and he grew up to become an landowner, carpenter, and entrepreneur. According to census records, by 1850, Jonas had moved out of his father’s home in Northampton County and was living with a painter named Andrew Reynolds—another free person of color—in Hertford County. Jonas was presumably either working for Mr. Reynolds as a carpenter or learning new skills as an apprentice to a painter.

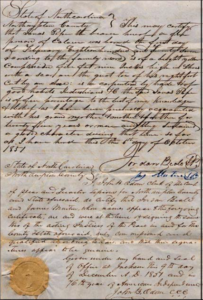

As a free person of color whose freedom was fragile in the best of circumstances, living away from the place where people knew you and respected your right to freedom could be dangerous. One of the early records that attest to the hardships endured due to that precarious situation was Jonas Pope’s Freedman’s Papers: According to Kenneth Joel Zogry, Pope’s Freedman’s Papers, dated October 6, 1851, were “written on sturdy vellum and carrying the notarized seal of the State of North Carolina…[and] offer poignant testimony to the fragility of life for free people of color in the decades preceding the Civil War. Age-darkened lines mark the neat creases of being repeatedly folded and unfolded, [which serves as] silent evidence that Jonas Pope carried this document with him at all times when off his own land, lest he be taken and sold…into slavery” (The House that Dr. Pope Built, 18). Pope’s papers contain a sworn statement by James Beale, a prominent white citizen, who attested that “the said Jonas Pope is a free person of color, to the best of my knowledge, as I have known his father, mother, and grandmother for many years” (quoted by Zogry, 19). Beale went on to affirm that Pope’s character was respectable, describing his as was “industrious, hardworking, & etc. & etc.” (quoted by Zogry, 19). As for his appearance, Jonas was described as “of bright yellow complexion, five nine inches in shoes, with a scar on the great toe of his right foot, cut by an axe.” The phrase “bright yellow complexion” indicated that Pope’s skin tone was obviously darker than the average Caucasian’s but lighter than the average African American’s and was language often used to describe a person of mixed-race heritage.

In July of 1853, Jonas purchased 321 acres of land near Rich Square from James Revell for $700 (Zogry, 26). That land became the place where he built his home and established a farm of his own. That December, he sold 121 acres of that tract for $420 to Silas Tallow, a neighbor with an adjoining farm, making a profit of about $50 (Zogry, 27). With that profit and his other income, Jonas constructed a fine house along the southern edge of his property. The two-story house was meticulously constructed and finished with elegant Greek Revival details, such as a front porch that was supported by turned columns and corner boards that resembled pilasters. Although changes were made throughout the years and now in ruins, the original house probably had five to seven rooms, and there was a chimney at each end of the structure. The house served as a testimony of Jonas’ skills as a carpenter and of his prosperity. According to Zogry, “few North Carolina families in the decades before or after the Civil War—white or black—lived in a home as commodious and refined as the one built by Jonas Pope in the mid-1850s” (26).

In 1858, Jonas married Permelia Pheobe Hall. Not much about Permelia’s life before her marriage to Jonas is documented. However, the Pope family has passed on stories about her through their oral traditions: According to her granddaughter, Ruth Permelia Pope, Permelia was “of free birth, her family never experienced the perils of slavery…her educational training was above the average, and she, like her husband, was artistically inclined. After work hours she would do much needle work…in the winter she made all of the clothing and the household linens” (quoted in Zogry, 27). According to census records, Permelia was born in 1829.

Permelia and Jonas had a son, Manassa Thomas Pope, on August 24, 1858. According to the 1860 census, the Popes still resided near Rich Square, and Jonas was a thirty-two-year-old carpenter who owned about $800 worth of real estate. Permelia, 31, and Manassa, 2, were also listed. Plus, the Popes had two other people living in their household at that time: Martha Colton, 17, and Joshua Scott, 16, were both listed as farm laborers. It seems obvious that Jonas was doing well for himself and his family. Zogry states that “carpenters…were the highest paid [free Black] tradesmen during the antebellum era [in North Carolina], earning an average of $323 annually by 1860.” (19).

During the 1860s, the war raged on, but little is known about how the Pope family was affected. Although Jonas did not join either army, his younger brother, Axom, served in the Union Navy (Zogry, 29). There were skirmishes throughout North Carolina, and since the Pope family lived close to the Virginia line, they were most likely affected adversely in some ways, whether it be worrying for their family members’ safety or suffering from the stress of protecting themselves from the dangers experienced by free people of color. However, they may have been isolated from some of the hardships that affected many North Carolinians during the war, too, since they were closely tied to their local community and somewhat self-reliant. Jonas’ father died during the war, and in 1863 Jonas paid the $320 needed to settle Elias Pope’s estate and retain ownership of his father’s land (Zogry, 29). To be able afford such an expense during the war speaks to the Pope family’s financial stability and resiliency.

According to the 1870 census, forty-three-year-old Jonas was still a carpenter with about $800 in real estate, and Permelia, 42, was “keeping house” and taking care of Manassa, who was 12 years old. The Popes also had two other people living in their home: 17-year-old George Manly, a farmhand, and Mary Manly, 15, who was listed as a “domestic,” helping Permelia around the house. The Manlys may have been siblings.

Ten years later, according to the next census, Jonas, 53, Permelia, 52, and Manassa, 21, all still lived in their home near Rich Square. Nine-year-old Atlas A. Colier also resided with them, either helping around the farm of apprenticing as a carpenter under Jonas. By that time, Jonas owned a considerable amount of land in Northampton County and Bertie County and was known as an excellent craftsman and carpenter. According to Zogry, Jonas bought at least twenty tracts of land in Northampton County between 1854 and 1892, selling most for a profit but improving several parcels for himself or renting sections out to sharecroppers, who mostly produced cotton. Jonas was also active in politics in the 1880s: He served as a delegate to the Republican State Convention, which was held May 1, 1884, at Raleigh.

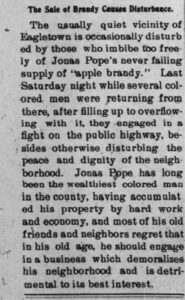

Although the exact date is unknown, records verify that Permelia died of unknown causes after 1880 but before February 1897. Zogry states that Permelia died in 1889 (p 119). By February 1897, Jonas, then 70 years, had married Northampton County native Mattie T. Reynolds, who was about 30 years old. At that time, his 39-year-old son, Manassa, had graduated from medical school, had established his own medical practice, and was married to Lydia Walden Pope. Jonas was still a very prosperous landowner/farmer and garnered much respect in his community. He also made and sold apple brandy, to the delight of many and the dismay of others in the area. (see article dated Feb 3, 1898).

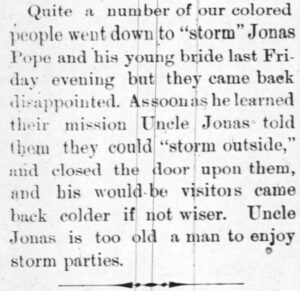

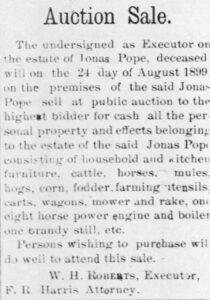

Jonas and Mattie had a son, Jonas Elias Pope Jr., on January 18, 1898. Unfortunately, Jonas did not get much time with his youngest son: The elder Pope died before July 11, 1899, at the age of 72. He was survived by his wife Mattie T. Reynolds Pope, and his sons, Dr. Manassa Thomas Pope and Jonas Elias Pope Jr.

The members of the Pope family are examples of the skilled, ambitious, and smart free people of color who lived successfully during the antebellum and the war years in North Carolina, despite the many societal and legal limitations they had to overcome.