Researched and Written by Cheri Todd Molter and Kobe M. Brown

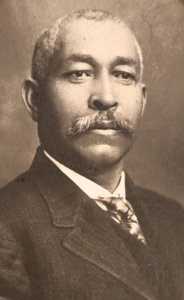

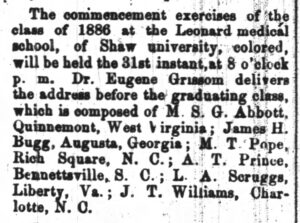

Manassa Thomas Pope was a free person of color born near Rich Square in Northampton County, North Carolina in 1858. Both of his parents, Jonas Elias Pope and Permelia Pheobe Hall Pope, were free persons of color, as was his paternal grandfather, Elias Pope. His father, Jonas, was a carpenter by trade and owned a large amount of land in both Northampton and Bertie Counties. In 1874, Manassa traveled to Raleigh to pursue higher education at Shaw University, a historically Black college that was established in 1865. After finishing his undergraduate education, he came home and was listed as living in his parents’ household in the 1880 census. Afterward, he began to study at the Leonard School of Medicine at Shaw University, the first four-year medical college in the state of North Carolina and graduated in March of 1886. (The News and Observer’s commencement announcement attached, March 26, 1886)

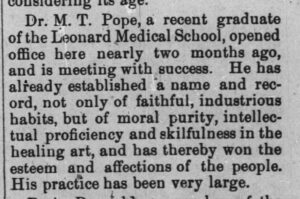

In August 1886, Dr. Manassa T. Pope established a medical practice at Raleigh. His office was located on East Hargett Street, which was historically known for being a major hub for Black businesses. According to a contributor to the African Expositor, a Raleigh newspaper, Dr. Pope had already successfully situated himself within the community and gained a good reputation within just a couple of months of his arrival. (article from Oct 1, 1886 attached)

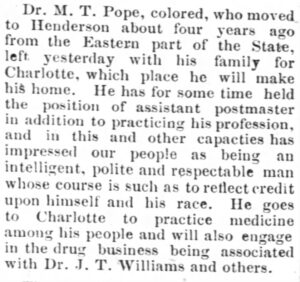

On February 23, 1887, Dr. Pope, married Lydia W. Walden at Hertford, North Carolina. By March 15, 1888, Dr. and Mrs. Pope settled in Henderson, North Carolina, moving his medical practice as they went. The editor of the Henderson Gold Leaf published an announcement, endorsing Dr. Pope and his abilities after the Popes’ arrival. Dr. Pope served as an assistant postmaster there for several years. About 4 years later, on April 20, 1892, Dr. Pope and Lydia left Henderson, moving to Charlotte, North Carolina.

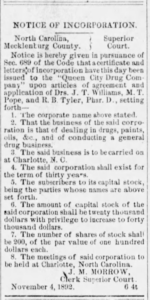

Once in Charlotte, Dr. Pope and his classmate from medical school, Dr. J. T. Williams, decided to work together to establish the Queen City Drug Company. In November 1892, Dr. Pope, Dr. Williams, and a few other men took the necessary steps to incorporate their drug store (The Charlotte Observer, Nov.6, 1892, p 4).

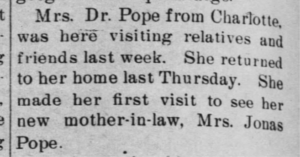

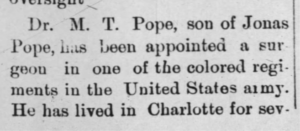

In June 1897, Mrs. Lydia Pope traveled to Northampton County to visit family, friends, and her father-in-law’s new bride, Mrs. Mattie Reynolds Pope. Her visit was documented by the local paper, The Patron and Gleaner. About a year later, Dr. Pope was traveling for a different reason: He enlisted in the U.S. Army, serving as an assistant surgeon for the Third Regiment of North Carolina Volunteers, an all-Black unit, during the Spanish American War. The unit never saw combat, and Dr. Pope mustered out of service in 1899, after reaching the rank of first lieutenant.

After that, Dr. Pope moved back to Raleigh. It was during that time that Democratic lawmakers had increased their efforts to disenfranchise African Americans in North Carolina; however, Dr. Pope was able to present his father’s, Jonas Elias Pope’s, 1851 Freedman’s papers to a voter’s registration office to verify that he met the voting criteria. Therefore, Dr. Pope was issued a voter registration card and was one of the 7 men of color who were able to vote in the city of Raleigh at that time.

In 1906, Mrs. Lydia Pope died from tuberculosis. She and Dr. Pope had never had any children. A year later, Dr. Pope married Delia Haywood Phillips. They had two children: Evelyn B. Pope, born in 1908, and Ruth P. Pope, born in 1910. In the spring of 1919, Dr. Pope ran for mayor of Raleigh. Although he did not win the election, he received 126 of the cast ballots, and 98 of them came from the second division of the Third Ward, which was a primarily African American neighborhood then. Dr. Manassa Thomas Pope died in 1934 when he 76 years old.

Dr. Manassa Thomas Pope was a role model to a new generation of African Americans, those coming of age after the Civil War, after enslavement, and after emancipation. That new generation challenged the age-old prejudices and societal stereotypes that dominated the American south: They pursued higher education, took part in business ventures, and participated in politics. Dr. Pope and many others like him in the emerging Black middle class struggled to demonstrate to fellow African Americans that a higher quality of life was possible despite the Jim Crow laws and the menace of white supremacy terror tactics. The Pope House Museum in Raleigh serves to connect today’s public with the history of the respected and successful Pope family.