Written by Mary E. C. Drew; Edited and vetted by Cheri Todd Molter and Kobe M. Brown

In 1831, just over three decades before Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation ended slavery in America, an enslaved Virginian named Nat Turner, along with a group of armed enslaved revolutionaries, embarked on a bloody mission to reject and end the institution of slavery via an armed struggle. The revolt, which left some sixty Southampton County residents dead, rocked the foundation of the slaveholding South, and shattered its complacency forever.

In 1831, just over three decades before Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation ended slavery in America, an enslaved Virginian named Nat Turner, along with a group of armed enslaved revolutionaries, embarked on a bloody mission to reject and end the institution of slavery via an armed struggle. The revolt, which left some sixty Southampton County residents dead, rocked the foundation of the slaveholding South, and shattered its complacency forever.

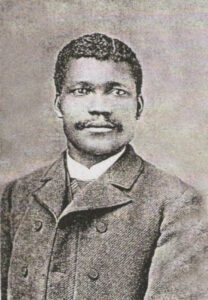

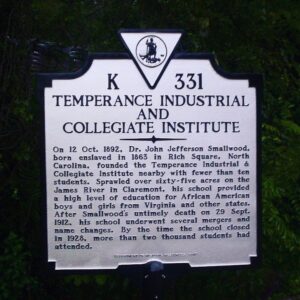

Over a half-century later, Dr. John Jefferson Smallwood, grandson of Nat Turner, founded the Temperance, Industrial and Collegiate Institute, a school designed to instill “Temperance and Morality, Industry, and Economy, Intelligence, and Race Pride” in American Blacks. His aim was to support and empower “intelligent men, and women” among the people of his race so that Blacks across the country could reach their full potential as citizens and as Americans. Dr. Smallwood preached a message of non-violence and strove to bring about a revolution in American society by uplifting the people of his race with a message of encouragement for them to elevate themselves through education, work, and self-pride.

Born on September 19, 1863, in Rich Square, Northampton County, North Carolina, John Jefferson Smallwood was the fifteenth of sixteen children that included nine sons and seven daughters. His mother was Mary Elizabeth Smallwood, the enslaved daughter of Nat Turner, and his father was David Jefferson Smallwood, who was also enslaved. When he was five months and ten days old, a slave trader purchased John Jefferson’s mother and father, thus separating him from his parents. His siblings were also sold and relocated to various parts of North Carolina, Virginia, and other states, but John Jefferson remained on the plantation of his original enslaver, Marcus Smallwood.

John Jefferson Smallwood spent the first years of his life on the plantation where he was born. From an early age, he yearned for the chance to go to school, an opportunity that had been forbidden to most Blacks, both enslaved and free. But his fortune changed after an event that occurred at the close of the war. When Union Troops invaded Rich Square, the elderly plantation owner, Marcus W. Smallwood, was assaulted. Two-year-old John Jefferson was there and pleaded successfully for them to spare Smallwood’s life, thereby stopping the violent encounter. In gratitude, the elderly man arranged in October 1870 for him to attend the Butler School, which was one of the first schools established in the United States for African Americans. In June 1871, Marcus W. Smallwood died, and without his financial support, seven-year-old John Jefferson was told not to return to Butler School.

A few years later, determined to pursue higher education, John Jefferson excelled at Hampton and Shaw, and even at Wesleyan Academy, an institution attended by predominantly white men at Wilbraham. Despite the harassment and racial prejudice he encountered there, he persevered. A polished orator, he became a teacher, a preacher, and an international speaker on race relations. While studying at London’s Trinity College, he conceived of founding an institution to educate African Americans and their children. A year later, on his return to the U.S., he purchased land in Surry County, Virginia, on which to build the school he had dreamed of. In October of 1892, his Temperance, Industrial and Collegiate Institute opened, with fewer than ten students and less than fifty dollars in actual cash.

For the rest of his life, Dr. Smallwood labored intensely to maintain his school, which continually grew, even in the face of daunting financial difficulties, personal losses, and the prejudice of the local community. As principal of Temperance, Dr. Smallwood delivered lectures on race relations throughout the United States and abroad, and he corresponded with such iconic American figures as Frederick Douglass, Booker T. Washington, and Elizabeth Cady Stanton. His story is part of the rich fabric of history that helped shape the nation’s perceptions of race and race relations during the Reconstruction years. That’s why I published two different books about my ancestor.

For the rest of his life, Dr. Smallwood labored intensely to maintain his school, which continually grew, even in the face of daunting financial difficulties, personal losses, and the prejudice of the local community. As principal of Temperance, Dr. Smallwood delivered lectures on race relations throughout the United States and abroad, and he corresponded with such iconic American figures as Frederick Douglass, Booker T. Washington, and Elizabeth Cady Stanton. His story is part of the rich fabric of history that helped shape the nation’s perceptions of race and race relations during the Reconstruction years. That’s why I published two different books about my ancestor.

First, there’s Divine Will, Restless Heart: The Life and Work of Dr. John Jefferson Smallwood, which follows Dr. Smallwood from his birth into enslavement, through his emancipation in rural North Carolina, his struggle to earn an education, his establishment of the Temperance, Industrial and Collegiate Institute, to his untimely death at the age of forty-nine. The account is enhanced by anecdotes and quotations from original correspondence found in archival collections of Dr. Smallwood’s papers and in the written and oral records passed down through the Smallwood family and shared with me, Dr. Smallwood’s great-great-niece. The book not only illuminates his role as an early civil rights advocate but provides an in-depth look into the life experiences of one African American man who succeeds during a time of extreme racial strife and upheaval and how he miraculously overcame the seemingly insurmountable odds.

Collegiate Institute, to his untimely death at the age of forty-nine. The account is enhanced by anecdotes and quotations from original correspondence found in archival collections of Dr. Smallwood’s papers and in the written and oral records passed down through the Smallwood family and shared with me, Dr. Smallwood’s great-great-niece. The book not only illuminates his role as an early civil rights advocate but provides an in-depth look into the life experiences of one African American man who succeeds during a time of extreme racial strife and upheaval and how he miraculously overcame the seemingly insurmountable odds.

My second publication is entitled One Common Country for One Common People: Selected Writings and Speeches of Dr. John Jefferson Smallwood. Before Dr. Smallwood became founder and president of the Temperance, Industrial and Collegiate Institute, he had already made a name for himself as one of the most eloquent African American orators in America and England. As a result, Dr. Smallwood was no stranger to the lecture circuit. From 1886 until his untimely death in 1912, he was a familiar face on the platform, giving lectures throughout the United States and abroad on the experiences of the “American colored man.” Relying on archival collections of Dr. Smallwood’s papers from multiple locations and incorporating written and oral records passed down through the Smallwood family, I made every attempt to provide a complete compilation of some of the most significant and poignant of Dr. Smallwood’s speeches and writings, dating from the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.