A Woman’s Perspective: While the Men Were Fighting

(Source: Contributed by Ms. Julia Moody Britt)

(Source: Contributed by Ms. Julia Moody Britt)

Mary Susan Morrow and David Vanhook died of typhoid fever within a week of each other, leaving four small children to be reared by the maternal grandparents, Ebenezer and Paletiere Clement Morrow.

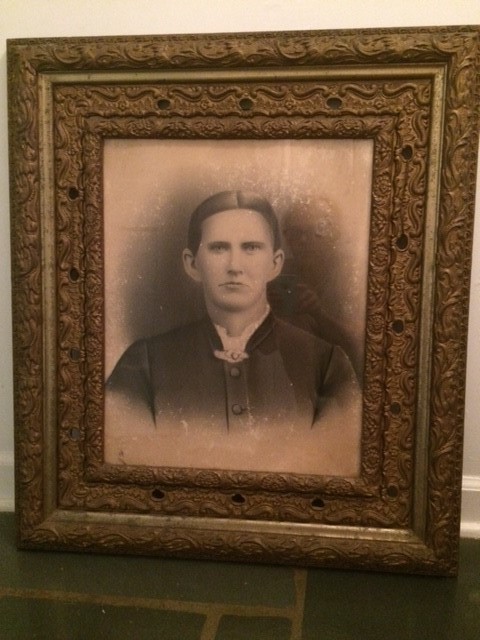

When Sarah Jane, the eldest, was 16 and attending school in Franklin, she climbed out of a window at Dixie Hall to elope with Nathaniel Henderson Parrish. They had a son before Nathaniel and four of his brothers joined the Confederate army and went off to fight in the Civil War.

When Sarah Jane had their second child, daughter Pallie, Nathaniel came home (the Morrow house on Highway 28 North in Franklin, NC). While he was there he was accosted either by Northern troops headed for Atlanta and Sherman, coming out of Tennessee, or Kirk’s Raiders. They made Sarah Jane get out of bed and open trunks, they ran the slaves off into the woods, and they strung Nathaniel up in a tree before heading down the road. An uncle and the slaves came back, cut Nathaniel down, and eventually he was able to go back to the war with only slight damage to his vocal cords, leaving Sarah Jane with two small children and the help of grandparents.

The war ranks and service records of the five Parrish brothers, this hanging incident when Nathaniel came home for the birth of his daughter, and their subsequent lives after all five returned home safely after the war have been well covered in Volume I of Macon County History and some in Volume II, as well. Ron Bateman, the grandson of Wade Parrish who went West to Utah and became a rancher, has written an excellent history, Across Three Centuries of the Nathaniel H. Parrish Family, that contains many pictures and interesting facts and records.

After Nathaniel came home, Sarah Jane bore them 10 more children. Shortly after giving birth to Sally, the 12th child, who died at about two months of age, Sarah Jane also died, at age 45. The two are buried side by side at Cowee Baptist Church cemetery in Franklin.

After Sarah Jane died, care of the younger Parrish children fell largely to my grandmother (for whom I was named), Julia Emaline Parrish, who married Jubal Early Calloway, and her sister Carrie Anne Parrish, who married Dan Lyle.

Before Julia was married, her father Nathaniel married another 16-year-old girl, Laura Jane Hall, gave Julia, Carrie, and Pallie the property on Highway 28 North where he and Sarah Jane had lived, and moved to his land on Rose Creek. There he and Laura had five more children, giving Nathaniel 17 children in all. When Nathaniel died, Laura buried him in Cowee Baptist Church Cemetery, near Sarah Jane and Sally. She later married his brother, George Washington Parrish, whom she cared for until he died. Oh, the remarkable strength and devotion of Civil War women!

Indeed, down through the years, the Parrish family has been characterized by strong women. Nathaniel’s father, John Henderson Parrish, married Ruth Ann Carrington, who was the daughter of Nathaniel Carrington and Anna Davis, the aunt of Confederate President Jefferson Davis. Ruth Ann was also the granddaughter of Revolutionary War veteran John Carrington. My grandmother Julia always said that the seven slaves who came to Franklin with John, Ruth, and their eight children in 1849 belonged to Ruth Ann, and they were probably the ones who came to Nathaniel’s rescue when he was hanged. When the war ended, Nathaniel gave each of the slaves a parcel of land and helped them build houses. Many of the former slaves also took the Parrish and Morrow names.

Another interesting note is that Ebenezer Morrow was directly related to Anne Morrow Lindbergh’s father, but I can’t say exactly how.

From inheritances from his father and mother and from land grants of as many as 200 acres of Cherokee lands, Nathaniel, Laura, and his 16 surviving children lived very well after the war.

Grandmother Julia was older than her new stepmother when she married Jubal Early Calloway, and Nathaniel gave her a beautiful sidesaddle for a wedding present. She never knew whether it was her mother’s or whether Nathaniel had bought it new, but she treasured it all of her life. It eventually came to me, and I wrote the North Carolina Museum of History in Raleigh to ask if they would like to have it. I received a quick reply saying that they had four or five sidesaddles, but if I would send a picture and the story that went with it, they would quickly replace one of their five with it because they had so little from the western part of the state. I eventually loaned it to the Macon County Historical Society to go in Cowee School, where my mother, Lily Calloway Moody Cabe, taught for years until she retired, and where I felt she would be proud for it to be displayed in “home” territory.

However, remembering what I was told in Raleigh, I want to be sure that the five Parrish brothers and the women who loved them and gave them a rich and enduring legacy are recognized in the Fayetteville Civil War museum (the North Carolina Civil War History Center), and that the western part of the state is well represented there.