Submitted by Matthew Howell; Vetted by Cheri Todd Molter and Kobe M. Brown; Edited by Cheri Todd Molter

In Fayetteville, known as Cross Creek until 1778, there are many old cemeteries.[1] The oldest is the first Cross Creek Cemetery, which was established in 1785.[2] Among the many headstones, there is one with the name “George C. Beasley” engraved on its surface. The inscription reveals that George was the son of J. M. and M. Beasley and that he died at the age of 25 in battle at Fort Harrison in 1864. During the American Civil War, millions of people caught up in the turbulent waters of societal change left their homes to support the war effort. Roughly 125,000 young men from North Carolina—like George C. Beasley—went off to fight for the Confederacy, and over 40,000 of those young men never returned.[3] Indeed, each person had their own unique story, many of which are gone forever.

George was born on April 30, 1839, in Cumberland County.[4] He was the first-born child of John Mebane Beasley and Mariah Holmes.[5] The Beasleys had six children, four of whom survived past early childhood: George, Arabella, James, and Benjamin.[7] Although George and James both died as young men,[8] Arabella lived 71 years, and Benjamin lived to be 94 years old.[9]

Not much is known about George Beasley’s early life; however, records verify that he enlisted in the Confederate army on April 17, 1861, just 13 days before his 22nd birthday.[10] He served in Company F, 1st North Carolina Infantry, and his first duty was to assist in the takeover of a critical location in his hometown, the U.S. Arsenal.[11] The arsenal had been constructed in 1838 and, during the Civil War years, it was a major supplier of rifles and other small arms to the Confederate army.[12] At the start of the war, the arsenal was under Federal command. George, and approximately 500 additional Confederate soldiers, assembled at the arsenal on April 22, 1861.[13] Federal forces gave up the site without incident, and the U. S. Arsenal became known as the Fayetteville Arsenal and became a key production facility for the Confederate States of America (CSA) until it was taken and burned by General William T. Sherman in March 1865.[14]

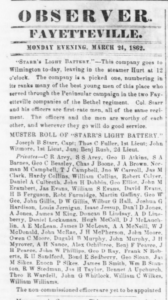

After the takeover of the U. S. Arsenal, George traveled with his company into Virginia and was stationed at the Big Bethel Church near Fort Monroe.[15] On June 10, 1861, they participated in their first battle, the Battle of Big Bethel, which was one of the earliest battles of the war.[16] George’s company remained on the Virginia peninsula until the regiment disbanded and returned to North Carolina in November 1861.[17] He returned home for the winter, and in the spring of 1862, he volunteered to be a part of Company B, 2nd North Carolina Light Artillery.[18] That company was referred to as Starr’s Light Battery.[19] It was led by Captain Joseph B. Starr, a Fayetteville native who had participated in the takeover of the arsenal the prior spring.[20]

On March 24, 1862, George boarded the steamship Hurt with the rest of his company and traveled down the Cape Fear River to Wilmington.[21] From there, they moved up through North Carolina, on their way to Virginia. In December 1862, Starr’s Battery participated in the Battle of Kinston Military Park.[22] Union forces were moving through North Carolina, attempting to disrupt Confederate supply chains. Kinston was ultimately captured as Confederate forces were overrun and forced back across the Neuse River.[23]

On March 24, 1862, George boarded the steamship Hurt with the rest of his company and traveled down the Cape Fear River to Wilmington.[21] From there, they moved up through North Carolina, on their way to Virginia. In December 1862, Starr’s Battery participated in the Battle of Kinston Military Park.[22] Union forces were moving through North Carolina, attempting to disrupt Confederate supply chains. Kinston was ultimately captured as Confederate forces were overrun and forced back across the Neuse River.[23]

By the spring of 1863, George and the rest of Starr’s Battery had made it into Virginia and by the summer, they were in Pennsylvania. For the remainder of that year, they participated in some of the most vicious battles of the Civil War. George, far from home, witnessed the horrors of battle at Bull Run, Fredericksburg, and Gettysburg.[24] From March 1862 to the winter of 1863, George traveled extensively and engaged in many conflicts.

In November 1863, Starr’s Battery was merged into the 13th North Carolina Artillery Battalion, and Captain Starr was promoted to Lieutenant Colonel on December 1, 1863.[25] It was at this time that George Beasley’s military career made an interesting pivot. In December of 1863, instead of joining his company in the 13th Artillery, George transferred to the 51st North Carolina Infantry.[26] Records show George detached from the ranks from April 1864 through the end of August 1864.[27] During this time, he was on duty in the regimental commissary, Captain H. B. Lane.[28]

By the end of the summer, George was back in the ranks as a Private in the 51st NC Infantry.[29] The long Siege of Petersburg was underway and Lt. General Grant was executing his assault on the weary Confederate army. In between Petersburg and Richmond was Fort Harrison, a key position on the Confederate lines overlooking the James River.[30] The Union forces had taken the fort on September 28, 1864, and Gen. Lee ordered a counterattack the following day.[31] George and the rest of the 51st NC Infantry were called in for the counterattack.[32] However, the Confederates failed, and George sustained a serious wound to his shoulder during the attack.[33] By that evening, he was transported to the Receiving & Wayside Hospital outside of Richmond.[34] After his initial treatment, he was transferred to Winder Hospital in Richmond for further care.[35] Winder was the largest hospital in the Confederacy, with the resources necessary to provide advanced care.[36] George died on October 26, 1864 of pneumonia.[37] At just 25 years of age, George joined the list of about 40,000 North Carolinian soldiers who died during the war.

Although George was listed as being buried in the Confederate section of Hollywood Cemetery in Richmond,[38] his parents erected a headstone for him in the Cross Creek Cemetery in Fayetteville. The headstone reads, “George C., son of J. M. & M. Beasley, Died of a wound received at Fort Harrison, Aged 25.” However, the headstone at Cross Creek Cemetery may be a cenotaph, unless George’s parents were able to coordinate the relocation of his body back to Fayetteville after the war.

George’s father, John M. Beasley, was a well-known jeweler and clock maker in Fayetteville.[39] His shop was located on the northeast corner of Market Square in downtown Fayetteville.[40] Mr. Beasley regularly published advertisements for his fine jewelry, his clock and watch repair services, and his Colt firearms and Bowie knives in the Fayetteville Observer, which ran from 1816 until 1865.[41] The old clock tower, which still stands today, was repaired by Mr. Beasley in October of 1858.[43]

After John Beasley retired, Benjamin Franklin Beasley, his son, took over the family business and ran the Beasley Jewelry store at 103 Hay Street in Fayetteville well into the early 1900s.[44] In September 1886, John Beasley suffered a stroke that left him partially paralyzed.[46] He died a few years later, on August 13, 1889.[47] Mr. Beasley was buried at the Cross Creek Cemetery #1. Mrs. Mariah Beasley, who perished in 1895, was buried next to him.[48]

One of the many benefits of living in the digital age is the breadth of information accessible to the public. Much effort has been made to preserve historic records and documents. Fortunately, in the case of George Beasley, his military records survived the war and have been made available to the public. Between those records and other documentation, one can piece together an accurate story about his life. There is tremendous value in doing this research: Families are remembered, information is shared, questions are answered, and posterity reaps the benefit of that learning. Stories like George’s are valuable teaching tools: They allow educators to share relatable documented information, connecting future generations to people and events long passed. By doing so, the next generation can connect with universal truths about the human experience and their place in the world.

[1] Parker, “Cumberland County,” 22.

[2] “Marker: Cross Creek Cemetery,” North Carolina Digital Collections, https://digital.ncdcr.gov/digital/collection/p15012coll8/id/11022.

[3] “Wartime North Carolina,” Official Website of the State of North Carolina, https://historicsites.nc.gov/resources/north-carolina-civil-war/wartime-north-carolina.

[4] George’s birth and death dates were gathered from his headstone in the Cross Creek Cemetery at Fayetteville, North Carolina.

[5] “United States Federal Census Records, 1850,” Ancestry.com.

[6] “Fayetteville Observer, 1851-1865,” North Carolina Newspapers, https://www.digitalnc.org/collections/newspapers/.

[7] “United States Federal Census Records, 1870,” Ancestry.com.

[8] Headstone, Cross Creek Cemetery, Fayetteville, North Carolina. Find A Grave. https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/14403176/james-a-beasley.

[9] “U.S., Newspapers.com Obituary Index, 1800s-current,” Ancesty.com. https://www.ancestry.com/discoveryui-content/view/609323395:61843?ssrc=pt&tid=183504850&pid=262389842647; “California, U.S., Death Index, 1940-1997,” Ancestry.com. https://www.ancestry.com/discoveryui-content/view/464462:5180?ssrc=pt&tid=183504850&pid=262389842649.

[10] “George C. Beasley Compiled Service Records,” National Archives. Provided by Robert Krick, Chief Historian, Richmond National Battlefield Park, National Park Service.

[11] Parker, “Cumberland County,” 52.

[12] Parker, “Cumberland County,” 74.

[13] “Fayetteville Observer, April 25, 1861,” North Carolina Newspapers, https://newspapers.digitalnc.org/lccn/sn84026542/1861-04-25/ed-1/. “George C. Beasley Compiled Service Records,” National Archives. Provided by Robert Krick, Chief Historian, Richmond National Battlefield Park, National Park Service.

[14] Parker, “Cumberland County,” 70.

[15] “George C. Beasley Compiled Service Records,” National Archives. Provided by Robert Krick, Chief Historian, Richmond National Battlefield Park, National Park Service.

[16] Ibid.

[17] “George C. Beasley Compiled Service Records,” National Archives. Provided by Robert Krick, Chief Historian, Richmond National Battlefield Park, National Park Service.

[18] “Fayetteville Observer, March 24, 1862,” North Carolina Newspapers, https://newspapers.digitalnc.org/lccn/sn84026542/1862-03-24/ed-1/.

[19] Ibid.

[20] Ibid

[21] Ibid.

[22] “George C. Beasley Compiled Service Records,” National Archives. Provided by Robert Krick, Chief Historian, Richmond National Battlefield Park, National Park Service.

[23] Tyndall, “Lenoir County,” 57.

[24] “George C. Beasley Compiled Service Records,” National Archives. Provided by Robert Krick, Chief Historian, Richmond National Battlefield Park, National Park Service.

[25] Clark, “Histories of the several regiments and battalions from North Carolina, in the great war 1861-’65,” 112.

[26] “George C. Beasley Compiled Service Records,” National Archives. Provided by Robert Krick, Chief Historian, Richmond National Battlefield Park, National Park Service.

[27] Ibid.

[28] Ibid.

[29] Ibid.

[30] Clark, “Histories of the several regiments and battalions from North Carolina, in the great war 1861-’65,” 408.

[31] Ibid.

[32] “George C. Beasley Compiled Service Records,” National Archives. Provided by Robert Krick, Chief Historian, Richmond National Battlefield Park, National Park Service.

[33] Ibid.

[34] Ibid.

[35] Ibid.

[36] Betts, Vicki, “Richmond [VA] Whig, January-June 1864” (2016). By Title. Paper 108. http://hdl.handle.net/10950/756

[37] Ibid.

[38] Ibid.

[39] “Fayetteville Observer, 1851-1865,” North Carolina Newspapers, https://www.digitalnc.org/collections/newspapers/.

[40] “Fayetteville Observer, September 30, 1852” North Carolina Newspapers, https://newspapers.digitalnc.org/lccn/sn84026542/1852-09-30/ed-1/.

[41] Parker, “Cumberland County,” 70.

[42] “Fayetteville Observer, December 19, 1853” North Carolina Newspapers, https://www.digitalnc.org/collections/newspapers/. https://newspapers.digitalnc.org/lccn/sn84026542/1853-12-19/ed-1/.

[43] “Fayetteville Observer, October 7, 1858” North Carolina Newspapers, https://newspapers.digitalnc.org/lccn/sn84026542/1858-10-07/ed-1/.

[44] “Fayetteville Observer, January 30, 1908” North Carolina Newspapers, https://newspapers.digitalnc.org/lccn/sn91068142/1908-01-30/ed-1/.

[45] Headstone, Cross Creek Cemetery, Fayetteville, North Carolina. Find A Grave. https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/14403177/james-mebane-beasley

[46] “Fayetteville Observer, September 16, 1886” North Carolina Newspapers, https://newspapers.digitalnc.org/lccn/sn91068141/1886-09-16/ed-1/.

[47] Ibid.

[48] Headstone, Cross Creek Cemetery, Fayetteville, North Carolina. Find A Grave. https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/14403177/james-mebane-beasley