AUTHOR: Paul Peeples (edited by Cheri Todd Molter)

The U.S. Army Airborne and Special Operations Museum at Fayetteville, North Carolina, has many monuments and memorial paver stones on its grounds. Each one has a story behind it, and one is of a hometown hero named Alexander McRae. (Click on image to enlarge.)

The U.S. Army Airborne and Special Operations Museum at Fayetteville, North Carolina, has many monuments and memorial paver stones on its grounds. Each one has a story behind it, and one is of a hometown hero named Alexander McRae. (Click on image to enlarge.)

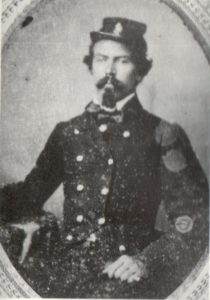

Alexander McRae was born in Fayetteville on September 4, 1829 to John and Mary Ann McRae. John McRae was the Postmaster of the town and had succeeded his father, Duncan, in the position. Alexander, known as Alec to his friends and family, attended Donaldson Academy and St. John’s Episcopal Church during his formative years in Fayetteville. At the age of fourteen, he enrolled in the Classical Course of studies at Newark Collage at Newark, Delaware. In 1847, he accepted an appointment to the United States Military Academy at West Point, New York. He graduated twenty-third out of a class of forty-two in 1851 and was assigned to the Regiment of Mounted Rifleman (RMR).

The RMR had been formed to provide security for travelers on the Oregon Trail, and most of its officers were appointed from outside the Regular Army line. For example, Captain Samuel Walker of the Texas Rangers, for whom the Walker Colt Pistol was named, was one of them. The RMR joined Scott’s Army in its expedition into Mexico and served with distinction, earning the title “Brave Rifles” from its commander. After the end of the Mexican War, the RMR was assigned to duties in Texas and the newly acquired territories in the Southwest.

Alexander served first at Ft. Merrill, then at Ft. Ewell along the Nueces River, then in West Texas for the next few years. He took an extended period of leave in 1856, returning to North Carolina, and then traveled to France to visit his older brother, Duncan K. McRae, who was serving as consul general to Paris. In 1857, Alexander was promoted to First Lieutenant and given command of Company E of the RMR in the New Mexico Territory. In the spring of 1858, his company and other elements of the RMR ventured from Fort Union, New Mexico, into Utah to support Colonel Albert Sidney Johnston’s punitive expedition against the Mormons. Returning to Fort Union in September, McRae was assigned to Recruiting Duty, based out of Carlisle Barracks, Pennsylvania. He went on leave to Fayetteville in the summer of 1859. During February and March of 1860, Alexander went to Kentucky to obtain horses for the Army. In August of 1860, he traveled back west with a detachment of recruits, remount horses, and recent West Point graduate Second Lieutenant Joseph Wheeler. After his return to the RMR, he was given command of Company K, which he led on a successful raid against a Kiowa camp located in the Indian Territory (near current Cold Spring, Oklahoma) in January 1861. That new year, however, was one of tragedy and challenges for this Tarheel native son.

Early in 1861, after Texas and some other southern states seceded from the Union, thirteen of Alexander’s brother RMR officers, including Second Lieutenant Joseph Wheeler and Captain Richard S. Ewell, resigned their commissions and joined the armed forces of the Confederate States of America. Incidentally, Alexander led a detachment of the RMR tasked with keeping the peace between ranchers and the Comanche along the Gallinas River region of New Mexico as Fort Sumter was fired upon by Confederate forces. On May 11th, Alexander’s mother, Mary Ann Shackleford McRae, died, and on May 20th, North Carolina seceded from the Union.

Four of Alexander’s brothers—Duncan Kirkland, James Cameron, Thomas Ruffin, and John—served in the Confederate Army. Duncan Kirkland McRae rose to command the 5th Infantry (North Carolina). James Cameron was already member of the Fayetteville Independent Light Infantry (FILI) when the war started. He participated in the Battles of Big Bethel, Williamsburg, and eventually served as a Major on General Lawrence Simmons Baker’s staff. James’ daughter, Mary Shackleford McRae, was one of the first women to attend the University of North Carolina. Alexander’s youngest brother, fourteen-year-old Robert, served with the Confederate blockade runners “Owl” and “Badger.” It is not hyperbole to say that the conflict of 1861-65 set brother against brother.

There were schisms among the residents of the Territory of New Mexico, too. Many Americans who lived on the land south of the Gila River, which was acquired in the Gadsden Purchase of 1853, had closer social, political, and economic ties with Texas and other southern states, than with the territorial capital of Santa Fe. Some had even petitioned for the area to be a separate territory. The towns of Mesilla and Tucson passed ordinances of succession in 1861. Confederate volunteers, led by a Colonel Baylor, journeyed from Ft. Bliss, Texas, to Mesilla, and then captured the Union garrison at Ft. Fillmore in July 1861.

Confederate sympathizers formed the paramilitary “Arizona Rangers” to fight Unionists and Indians. The lands south of the 34th parallel came to be called the Confederate Territory of Arizona. The battle lines were then drawn in the Southwest.

The scattered Regular United States Army garrisons in the New Mexico Territory consolidated at Fort Craig, by the Rio Grande in the center, and Fort Union, northeast of Santa Fe. Union volunteer units were raised in California and the Colorado Territory to provide reinforcements. The United States Army also reorganized its mounted units. The RMR was re-designated the Third U.S. Calvary in August of 1861.

Alexander, who was promoted to Captain in June of 1861, was sent to Fort Craig and served as Post Adjutant until November of that year. Afterward, he was given the task of forming a provisional Artillery Battery. That unit was composed of eighty-five Regular U.S. Army cavalrymen and six various field pieces and became known as McRae’s Battery.

The New Mexico Campaign of 1862 has often been obscured by the events that took place East of the Mississippi that year. The Battle of Valverde, where Alexander met his fate, is even more obscure. However, the following is a brief account of the Campaign, the part Alexander played in it, and its aftermath.

One of the U.S Army Officers who flocked to the southern cause at the start of the Civil War was Henry H. Sibley of Louisiana. He persuaded his fellow West Point graduate Jefferson Davis of the feasibility of raising a force in Texas for a campaign of conquest in the Southwest. As a Confederate Brigadier General, he oversaw the formation of a 3,500-man unit in the San Antonio area the summer of 1861. They started moving west, in stages, across the 750 miles between San Antonio and Ft. Bliss that October. By the end of 1861, they were camped along the banks of the Rio Grande near Fort Thorn, north of Mesilla, New Mexico. During the new year of 1862, they moved north to carve out a new empire for the Confederacy.

Opposing that invasion was a force of approximately 1,200 U.S. Army Regulars, 2,600 New Mexican Volunteer/Militia, and about 80 Colorado Volunteers at Ft. Craig under the command of Col. Edward R. S. Canby. Between the 12th and the 20th of February, Sibley’s forces maneuvered around Ft. Craig. They moved northeast around a large, dark, volcanic rock mesa to a ford of the Rio Grande at a place called Valverde, an oasis of grass and cottonwood trees in the rocky desert of New Mexico. Canby had already sent a part of his garrison out to secure the ford. He received word that the Confederates had arrived early on the 20th and dispatched the bulk of his forces, including McRae’s Battery, to engage them.

As dawn broke on the cold morning of February 21, 1862, Sibley’s Confederates engaged their opponents, holding the east bank of the ford. Union artillery and rifle fire dominated the field that morning, and Alexander’s six field pieces were backed up by a two-gun battery of 24-pound howitzers. There was a dramatic moment, reminiscent of Waterloo, when a company of mounted Texans, armed with lances, charged the Colorado Volunteer Infantry. The Coloradoans formed a square and repulsed them with a close-range volley of small arms fire. The bulk of Sibley’s men dismounted and took cover behind a low ridge overlooking the ford. There was a lull amid midday snow flurries when both sides replenished ammunition, ate, and gathered reinforcements.

Afterward, Sibley relinquished tactical command to Colonel Tom Green, an experienced veteran of the Texas War for Independence. He concentrated about 1,000 men behind the center of the ridge. Col. Canby arrived and took direct control of his forces. He redeployed McRae’s Battery to the center of his line, near a grove of cottonwood trees, and shifted other units right in preparation for the assault to sweep the Confederates from the ridge. Green saw that an 800-yard-wide gap had opened in the Union line and ordered an attack on the exposed center. The assaulting Confederates went over the ridge in three waves and dropped to the ground when guns fired at them, then they stood up and delivered a volley of small arms fire and pressed the attack. Alexander McRae was wounded but still tried to rally support and stood with his men. About 750 Confederates, some moving through the cover of the cottonwood trees, engaged the 250 remaining Union infantrymen and the 85 men of McRae’s Battery in a vicious melee. Canby sent support to his embattled center, but it was too late; the tide had turned. Alexander McRae and 18 of his men were killed. The Confederates turned the guns around on the retreating Union troops. Canby ordered a withdrawal back across the Rio Grande, then requested a truce to retrieve wounded and bury the dead. It was granted and lasted for two days. The Confederate Army lost 72 men who were killed in action, 157 men who were wounded in action, and about 1,000 horses and mules that were killed. Union losses totaled 111 men killed in action, 160 men wounded in action, and 204 men missing in action.

After the battle of Valverde, many of Sibley’s previously mounted troops were left afoot, and he had lost wagons and mules. He was forced to leave his sick and wounded behind in the nearby village of Socorro. Canby issued orders to his troops to “follow the enemy closely in his march up the valley, harass him in front, flank and rear with irregular troops and cavalry, burn or remove all supplies in his front, but avoid a general engagement, except where the position is strongly in our favor.” Union forces were successful in denying Sibley’s men the supplies and animals that they needed.

The 3rd U.S. Cavalry moved east later in 1862 and saw service in North Carolina before the war’s end. The Regiment became Armored Cavalry (3rd ACR) during World War II, and the tradition of service in the west has continued because it has been based at Fort Bliss, Texas, Fort Carson, Colorado, and Fort Hood, Texas. It participated in Operation Desert Storm in 1991 and peacekeeping operations in Bosnia in the 1990s. During its four tours of duty in Iraq between 2003 and 2011, it earned five Valorous Unit Commendations. In 2011, it was redesignated a Stryker Unit, so essentially, it is again a “regiment of mounted riflemen.” The ethos of service, sacrifice, and devotion to duty exemplified by Captain Alexander McRae still lives on with his regiment.

Alexander was praised by friend and foe alike for his conduct at the Battle of Valverde. One of the Texans who made the assault on the Union center at Valverde was Private William L. Davidson, Company A, 5th Texas Mounted Volunteers. Davidson, though born in Mississippi, had North Carolina roots through his Tarheel father. He also graduated from Davidson College, which had been named for his great-uncle, William Lee Davidson. Pvt. Davidson had this to say about McRae: “[H]e died by his guns and no braver man lived or died on that field. He was a Southern Man, a North Carolinian, but he died fighting the South, but he died where he thought his duty lead him.”

Furthermore, Alexander’s commanding officer, Col. Edward R.S. Canby, mentioned him in the official report he wrote to Washington on March 1, 1862: “Among these (casualties), however, is one isolated by peculiar circumstances, whose memory deserves notice from a higher authority than mine. Pure in character, upright in conduct, devoted to his profession, and of a loyalty that was deaf to the seductions of family and friends. Captain McRae died, as he had lived, an example of the best and highest qualities that man can possess.”

In 1863, the U.S Army named a post in New Mexico “Fort McRae,” which remained active until 1876. The site is now under the waters of Elephant Butte Reservoir, located near Truth or Consequences, New Mexico. Alexander’s remains were moved from New Mexico to the cemetery at West Point in 1867. McRae Blvd. was dedicated in El Paso in 1958. Located along that street is Eastwood High School, where a cannon is on display that is supposed to be one of the surviving guns of Valverde. In May 2013, a stone from Valverde was brought to Fayetteville, North Carolina, and a plaque commemorating Alexander’s life and service was attached to it. That stone is located at 130 Gillespie Street, the site of the McRae family’s residence during the early 19th century. (Click image to enlarge) Many McRae family descendants attended its dedication.

In 1863, the U.S Army named a post in New Mexico “Fort McRae,” which remained active until 1876. The site is now under the waters of Elephant Butte Reservoir, located near Truth or Consequences, New Mexico. Alexander’s remains were moved from New Mexico to the cemetery at West Point in 1867. McRae Blvd. was dedicated in El Paso in 1958. Located along that street is Eastwood High School, where a cannon is on display that is supposed to be one of the surviving guns of Valverde. In May 2013, a stone from Valverde was brought to Fayetteville, North Carolina, and a plaque commemorating Alexander’s life and service was attached to it. That stone is located at 130 Gillespie Street, the site of the McRae family’s residence during the early 19th century. (Click image to enlarge) Many McRae family descendants attended its dedication.