SUBMITTED BY: Alfred Ferguson

The following is an excerpt from a book that includes the letters written by my great-grandfather Lt. Franklin Murphy. He helped demolish the Fayetteville Arsenal.

An excerpt from Bernard A. Olsen’s (2000) A Billy Yank Governor, the Life and Times of New Jersey’s Franklin Murphy:

Murphy Reaches North Carolina

There was a major change among Sherman’s troops as they moved into North Carolina. Orders went out to avoid the wanton destruction of civilian property. North Carolina was not the cradle of secession but rather had been the last of the southern states to secede. Furthermore, significant numbers of her citizens had remained loyal to the Union. “As if the army had undergone a massive transformation overnight, North Carolinians received treatment similar to that of Georgians. Senior commanders issued orders to remind the soldiers that they were in North Carolina…a marked difference should be made in the manner in which those of South Carolina were treated.” Sherman had an ulterior motive as well. There had always been a degree of hostility between the peoples of North and South Carolina dating back to early colonial times. Sherman thought he could exploit these ancient animosities in his quest to divide and conquer. He wanted his men to “deal as moderately and fairly by the North Carolinians as possible, and fan the flame of discord already subsisting between them and their proud cousins of South Carolina. There was never much love between them. Touch upon the [South Carolina] chivalry running away, always leaving their families for us to feed and protect, and then on purpose accusing us of all sorts of rudeness.”

It had stopped raining by sun-up on March 9 as the men awoke in hopes that the weather would “clear off.” They were on the road by 8 o’clock and by 9 o’clock it started raining again. They continued on stopping and starting for another twelve hours encamping about 10:00 PM for the night. The rain finally tapered off and Murphy found the time to jot down a few lines in his diary. “Just after I had my tent pitched the rain ceased.

Matthews, Peirson & Bohwell took supper with me as their mule was not up. Mat & B slept with me.” March 10 and 11 saw the blue columns push onward wading across huge swamps and down roads knee deep in mud over the Lumber River on pine tree bridges near what is probably known as Blue Ridge. By late in the day of the 11th, Murphy and his comrades were moving out almost on a “double-quick.” He noted “We struck the plank road before dark and marched to within a mile & a half of Fayetteville where we camped having made 21 miles-the last 11 of which were made without halt or rest. We camped at 10 P.M.

The Confederates had about twenty-five thousand soldiers in Fayetteville and although they made statements of their intentions to defend the city, they evacuated it as the northern troops approached. Some of the rebels were sent to Jonesborough while the rest were sent to reinforce Raleigh. The military significance of Fayetteville was the city’s arsenal. It was one of the largest built by the United States Government spanning some twenty acres. One of Murphy’s comrades wrote:

There are about twenty brick shops of various sizes for the manufacture of ordnance, where we found some of the original machinery of the arsenal, besides some that had been brought from Harper’s Ferry by the rebels. These buildings and the dwellings, together with the machinery, ordnance manufactured, and materials for the manufacture, in all stages of completion, were all destroyed, most of them by the Michigan Engineers, with an ancient weapon-a battering-ram. We came so suddenly upon the enemy that they did not have time to remove any of it. The city had an old and dilapidated appearance; formerly contained about five thousand inhabitants. The rebels had destroyed six steamboats it being the head of navigation on the Cape Fear River.

March 12th

Laid quiet, In P.M. wrote a short letter home.

By March 13th the Federals had marched through Fayetteville and crossed the Cape Fear River on pontoons. Murphy was detailed to guard the flank of the brigade with the aid of a unit from the 107th New York Regiment. He found time to jot down in his diary his observations of Fayetteville.

“Fayetteville is quite a large sized town of five or six thousand inhabitants I should think. There is an old government arsenal-a very large & fine one which however Sherman is destroying. A very heavy line of works guarded the town from the South but it seems the enemy did not use them. We marched through town in column by company & were reviewed by Genl Sherman & Slocum.”

General Sherman did, in fact, destroy the arsenal at Fayetteville but he issued strict orders that the town was to be undisturbed otherwise. This policy of conciliation toward the people of North Carolina was in sharp contrast to the punishment meted out to their South Carolina countrymen.

March 14th

I passed the day on pickett. The Regt. & 2d Mass. Went on a recconnoissance [sic] some 9 miles up the road & returned about 10 P.M. I was relieved at dark & marched my detail to where the Regt. had camped & remained there for the night. Drew some cornmeal & bacon for them. Took supper with Clark.

There is an expression in military slang, “hurry up and wait” as orders are often countermanded or canceled entirely. This was certainly a feature of army life during the Civil War as well. It is difficult from the modern perspective to grasp the reality of what Murphy and his comrades endured in his relentless drive northward over unpaved roads and open terrain saturated by incessant rainfall. By March 15th another ten miles had been covered and the men took up position on the Cape Fear River near Bluff Church. The rain continued and the next five miles proved to be the most difficult of the entire campaign. Murphy wrote, “It rained in torrents from 1 o’clock till dark, but I got my tent up – had supper, & plenty of wood for a fire and was just making myself comfortable for the night when orders came to move immediately & I had to leave everything. In ten minutes we were off trudging through the mud on a five mile tramp to support Kilpatrick. The mud varied in depth from one foot to four feet & it was very sticky. Some shoes were lost in consequence. We had several streams to ford besides & with the intense darkness & the rain it was decidedly the most disagreeable night march the Regt. has ever had. We finally reached the Cavalry – took up position & made ourselves as comfortable as the mud would permit & waited for morning.”

Lieutenant Franklin Murphy moved out with his command from Fayetteville, North Carolina, on towards Averasboro in support of Federal cavalry under General Kilpatrick who was opposed by Confederate infantry. There were vast differences between the role of cavalry and infantry during the Civil War. Cavalry were generally considered the “eyes” of the army. It was their job to probe enemy positions, to wreak havoc on unprepared and unsuspecting foes and then report back vital information to army headquarters. It was their ability to cover vast distances relatively quickly that enabled them to function much like later day commandoes. The infantry, on the other hand, was the pivotal mainstay of the army; it was on their shoulders that battles were won or lost. Whether it was Johnny Reb and Billy Yank during the Civil War, or the doughboy, GI, or Grunt of later conflicts, it was they who bore the brunt of the fighting. It was the infantry “line of battle’ during the Civil War that constituted the strength of both armies. There were few instances where cavalry could stand up against infantry. General John Buford’s troopers were an exception at Gettysburg as were Nathan Bedford Forrest’s men at Brice’s Crossroads. These forces were dismounted and deployed as infantry much like the dragoons of earlier conflicts.

Battle of Averasboro

On March 16, 1865, the Second Brigade was moved up in line of battle on the right and left of the Raleigh Road – cavalry protecting the flanks. Skirmishes were sent out who quickly engaged the Confederates in what developed into the Battle of Averasboro. Captain Pierson detailed alternating units from each company of the 13th New Jersey Volunteers. They were followed by the Third Brigade which flanked the Confederate lines at the Second Brigade advanced to the front. By about 2:00 P.M. the whole line advanced. The 13th New Jersey Volunteers passing through a deep swamp and coming within two hundred years of the Rebel works engaged the enemy in desperate combat which lasted upwards of two hours. The Confederates abandoned their works and retreated in the direction of Goldsboro. The engagement cost Franklin Murphy’s regiment two men killed and twenty-two wounded. Among those who gave their last full measure of devotion were Wickliffe Hardman, and Orem Warren while Arthur Donnelly, James H. Parliament, and Cornelius Westervelt sustained lesser injuries.

March 16th

Soon after daylight the order was given to advance. We moved straight ahead our skirmishers driving the Rebels nearly or quite half a mile. Here they had a line of battle. We remained in this position some two hours during which the skirmishing was very heavy. Our line got out of ammunition & a new detail was sent out with Capt. Pierson. The rebels fired shells at us as well as bullets. Several of the men were wounded here. We were relieved here by the 3d Brig. of the 3d Div. & fell back & moved to the right where we engaged the enemy. After this we occasionally changed position forward or to the right but we were fighting all day – sometimes with only a skirmish line & sometimes with our whole line of battle, when the work was very warm. We drove the Rebels I should think a mile & a half during the day & captured from them 2 pieces of artillery. As we advanced we passed by a number of dead Rebs & several of their officers. It rained more or less all day. Just before dark we were relieved by a Brigade of the 14th Corps and we fell back and took up position in reserve. Camped in column by division. The loss of the Regt. was two killed – 21 wounded & 6 missing. Six of the wounded were from my company.

Sherman reflected on these events in a letter on March 17, 1865.

In the Field,

Camp between North River and Mingo Creek

March 17, 1865.

The enemy yesterday had a strong intrenched line in front of the crossroads, and had posted the Charleston Brigade about one third mile in front, also intrenched. The Twentieth Corps struck the first line, turned it handsomely and used the Charleston Brigade up completely, killing about 40 and gathering about 35 wounded and 100 well prisoners, capturing 3 guns, but on advancing further encountered the larger line, which they did not carry, but was abandoned at night. This morning a divisions of Williams’ followed as far as Averasborough [sic] whilst the rest turned to the right, as I have heretofore stated. Slocum lost in killed and wounded about 300. He is somewhat heavily burdened by his wounded, which must be hauled. We left the Confederate wounded in a house by the roadside. The route of retreat of the enemy showed signs of considerable panic, and I have no doubt he got decidedly the worst of it.

Yours truly,

W.T. Sherman

Major General

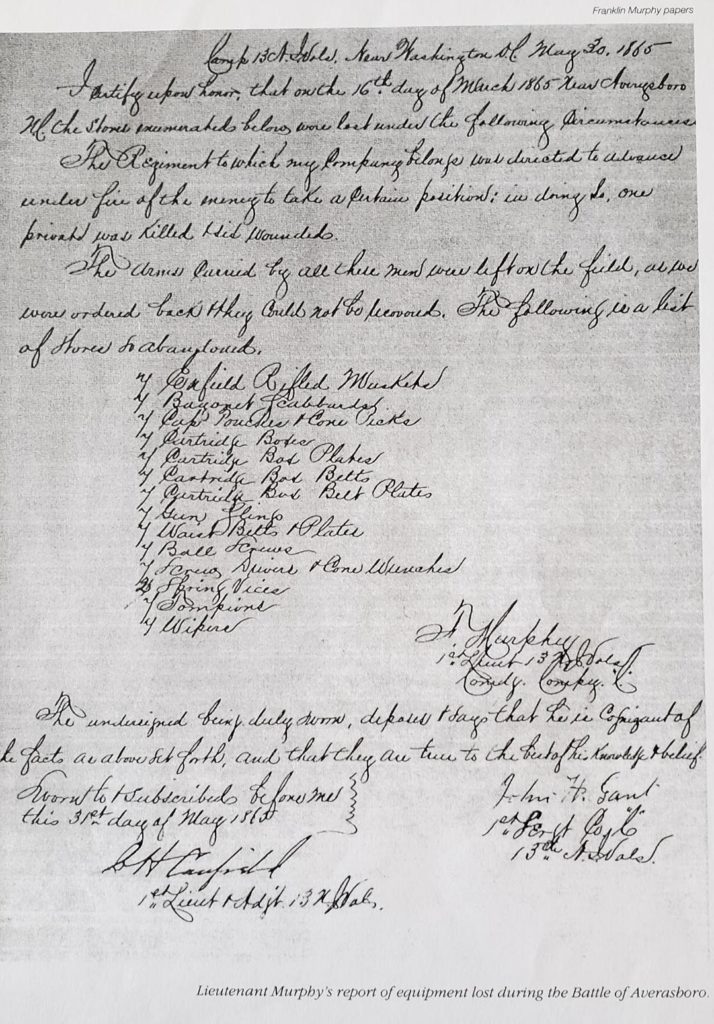

Equipment accountability has been a feature of the United States Army in times of war and peace. It would seem that under the immediacy of combat conditions that this accountability would be relaxed. This, however, has rarely been the case. For example, on at least two occasions Franklin Murphy in his capacity as Company Commander 13th New Jersey Volunteers documented material loss. The details are indeed remarkable if one contrasts the cumbersome methods of recording all arms and equipment during the Civil War with the efficiency of modern armories manned by highly trained M.O.S. (military occupational specialty) supply sergeants who collect special weapon cards before arms are issued. Murphy wrote the following report on equipment lost during the Battle of Averasboro:

“I certify upon honor, that on the 16th day of March 1865 near Averasboro N.C. the stores enumerated below were lost under the following circumstances.

The regiment to which my company belongs was directed to advance under fire of the enemy to take a certain position: in doing so, one private was killed and six wounded.

The Arms carried by all these men were left on the field, as we were ordered back & they could not be recovered. The following is a list of stores so abandoned.

7 Enfield Rifled Muskets

7 Bayonet Scabbards

7 Cap Pouches & Cone Picks

7 Cartridge Boxes

7 Cartridge Box Plates

7 Cartridge Box Belt Plates

7 Gun Slings

7 Waist Belts & Plates

7 Ball Screws

7 Screw Drivers & Cone Wrenches

2 Spring Vices

7 Tompions

7 Wipers

F. Murphy

1st Lieut. 13 N.J. Vols.

Comdy. Compy. C.”

The march continued as the blue columns made their way northward crossing the Black River on March 18th and through a hundred yards of chest-deep swamp. They stopped for about an hour. Murphy wrote, “on the other side and dried ourselves by the fire…we were working hard all day building corduroy roads. At dark we went to camp having made about 8 miles.”

Battle of Bentonville

Sherman’s army moved relentlessly onward despite Confederate attempts to impede its progress. Murphy and his comrades in the 13th Regiment New Jersey Volunteers were among the troops that were ordered to move on the 19th of March on the ‘double-quick” in support of General Slocum opposing General Johnston Near Bentonville. Major Harris was ordered to deploy the 13th New Jersey Volunteers on the right side of a ravine and to construct “such defenses as could be quickly made” to cover the rear of the 14th Corps. Heavy firing and retreating Federal soldiers indicated that the 14th Corps was in trouble and that a collapse was imminent. This, in turn, could become a rout which threatened to roll up the entire federal line. As hasty defenses were shifted to protect th right flank of the Regiment, the rebels emerged in three lines of battle from the woods into a cleared field a short distance to the left on the opposite side of the ravine. Lieutenant Murphy steadied his men to hold their fire until the rebels were within two hundred yards. Then came the order to fire unleashing a torrent of leaden hail, the fury of which was seldom seen during the whole campaign. …On came the gray line of battle plunging themselves headlong into the volleys of shot and shell. This was a true testimonial to the courage and dedication of these Confederate soldiers that underscores the assertion that these men, on both sides, possessed a unique quality of bravery and heroism…The southerners regrouped and advanced a second time again into the devastating fire of Murphy’s 13th New Jersey Volunteers. This proved too much even for these dauntless veterans as their morale collapsed and they retreated leaving their dead and dying on the field. Thus ended the Battle of Bentonville, yet another Union victory as the Federal pincers moved progressively northward. There were no further attempts by the Confederates to stem the advance of Sherman’s army. The Brigade commander, Colonel Hawley commended the 13th New Jersey Volunteers. “You are entitled to the thanks of this whole army, for you have saved it.”

The Thirteenth Regiment played a key role in this, the last battle of the war in the Carolinas. They foiled General Joseph Johnston’s attempt to overwhelm General Slocum before he could receive reinforcements. Had they not been able to stem the collapsing line, the battle most surely would have been lost. This, in turn, would have delayed for weeks the final victory over General Johnston’s Confederates and cost the lives of untold numbers of brave men, including perhaps Lieutenant Franklin Murphy. The 13th New Jersey Volunteers helped to bring the long war to a close yet their days of soldiering were not yet over.

Murphy recalled the Battle of Bentonville in his March 19th diary entry:

March 19th

We were off at the usual time this morning, and as usual, at work on the road which by the way was unusually bad as the 14th Corps passed over the same road ahead of us. About noon we heard artillery fire ahead of us some six mile which turned out the be the 14th Corps engaged with the enemy. We were soon after ordered forward as support and on coming up to the Battleground we took up position on the left of the 14th Corps our left retired in order to secure the flank. We had scarcely got in position before we heard the left of the 14th Corps was turned and the Johnnies were coming down upon us. We hastily threw up a few rails in front of us & had hardly done before the Rebs made their appearance in an open field on our left and front. They were in strong force (I should think a Brigade) & were coming to turn the flank of our 3d Brig. We gave them a very severe flank fire however & it was not long before they were running in the greatest confusion. We kept up the fire on them for some fifteen or twenty minutes & by the time we had driven them all back. The artillery – of which we had eight pieces in position on our right blazed away at them with grape & canister spherical case in front & we poured the bullets in their flank. After this the Rebs did not approach our works near enough for our fire to do much execution & we did not waste powder on them. They made an even distinct charge however just on our right & for three hours there was the loudest & most continuous musketry I ever heard. The slaughter on the part of the Rebs must have been tremendous for they charged against our works – which however slight afforded considerable protection to our men. The lines of the Rebels were in plain sight of our artillery and Batteries I & M 1st NY did their prettiest, I tell you. At dark the battle ended for by this time I judged the Rebs had enough of charging our lines. Col. Hawley, our Brigade commander gave the Regt. great credit for its action saying we saved the day for the troops on our right. After dark the men were at work strengthening the works, and by 10 o’clk [sic] we had a line that was consequently strong & the men lay down with their equipments on. I was very tired for I had worked hard during the day. There was but one man wounded in the Regt. He was Corporal Stark of my company.

Fall of Goldsboro

The men rested for the next two days occupying themselves with strengthening their defenses and cutting down timber. They removed as many trees in front of them as they could in an effort to deprive the advancing foe of cover. There was intermittent skirmishing on the picket lines, what they Federals referred to as a “brush with the Johnnies” but it did not amount to anything. By March 22 they were off marching about nine miles down the road towards Goldsboro and pushing on towards the Neuse River. Murphy’s friends Matthews and Kip “took supper and slept with me.” They reached the river about noon on the 23rd and passed General Terry’s command which consisted “of a division of the 24th, one of the 25th Corps,” about a mile from the river. “Saw Terry himself,” wrote Murphy.

March 24th

Pushed on at Daylight & reached Goldsboro about 9 A.M. While passing through the town we were reviewed by Gen. Sherman, Genl. Slocum, Schofield, Davis, Williams & several others were also present. We also passed Gen. Ruger & staff nearby. We pushed on through town & encamped about 3 miles outside. I was detailed for picket & went on duty about dark. I was senior officer and as the O.D. went away, I had to establish the whole line. It was a hard job and I did not get through till after nine o’clock.

On March 24, 1865, the 13th New Jersey Volunteers marched into Goldsboro with colors flying and drums beating passing in review of Generals Sherman and Slocum. Thus ended the campaign of the Carolinas. In seventy days the Union army had captured and destroyed millions of dollars worth of property, disrupted communications lines, and “made the mother-state of secession and rebellion feel in every nerve and fiber the war which she had causelessly provoked

Lieutenant Franklin Murphy’s last diary entry was on March 25th.

March 25th

Upon arriving in camp today, I found the Regt. had orders to build quarters where we were & thus ended our long campaign.

Captain Daniel Oakey, 2nd Massachusetts Volunteers, a member of the unit that Murphy respected, wrote of the Battle of Bentonville:

“As we trudged on toward Bentonville, distant sounds told plainly that the head of the column was engaged. We hurried to the front and went into action, connecting with Davis’s corps. Little opposition having been expected, the distance between our wing and the right wing had been allowed to increase beyond supporting distance in the endeavor to find easier roads for marching as well as for transporting the wounded… the Battle of Bentonville, which was a combination of mistakes, miscarriages, and hard fighting on both sides. It ended in Johnston’s retreat, leaving open the road to Goldsboro’, where we arrived ragged and almost barefoot. While we were receiving letters from home… Lee and Johnston surrendered, and the great conflict came to an end.”