WRITTEN by Leisa Greathouse; Edited and vetted by Cheri Todd Molter and Kobe M. Brown

Lewis Levy (1820-1899 pronounced Lee-vee) was an unwavering Unionist, property-owner, and businessman. Levy’s mother was considered a great cook: She prepared a meal for Lafayette when he visited Fayetteville in 1825. Lewis had been five years old then. Residents referred to his mother as “French Mary” because she was from the French province of Guadeloupe. Levy was listed as a mulatto on the census records. He was so light-skinned that he was arrested for not joining the Confederate Army. He was taken to Wilmington and examined by a Confederate surgeon who disqualified him “on the ground of physical inability.” Instead, he was conscripted to work at the Fayetteville Arsenal in 1862. The arsenal had been in the hands of the CSA since April 1861.

Lewis Levy (1820-1899 pronounced Lee-vee) was an unwavering Unionist, property-owner, and businessman. Levy’s mother was considered a great cook: She prepared a meal for Lafayette when he visited Fayetteville in 1825. Lewis had been five years old then. Residents referred to his mother as “French Mary” because she was from the French province of Guadeloupe. Levy was listed as a mulatto on the census records. He was so light-skinned that he was arrested for not joining the Confederate Army. He was taken to Wilmington and examined by a Confederate surgeon who disqualified him “on the ground of physical inability.” Instead, he was conscripted to work at the Fayetteville Arsenal in 1862. The arsenal had been in the hands of the CSA since April 1861.

Levy was a saddle and harness maker by trade. His skills were appreciated by the arsenal’s commanders. He was mocked, at least on one occasion, by a coworker for his devotion to the Union. Levy related the story to the claim’s commissioner: “One of the hands [the co-worker] moved a little paper U.S. flag over my head. I said that I never wanted any other flag to wave over my head…” It was risky for him to be outspoken about his support for the United States. Mr. E. Scurlock, a friend of Levy’s, heard “some say during the war that he ought to be hung for his sympathies for the Union cause and I heard some of his white friends say that if he did not mind [what he said] he would be hung for talking so plain in favor of the Union.”

He was vocal about the Union cause to his family, friends, and in the company of other free persons of color. That annoyed many whites in the area who supported the rebel cause. Levy blamed the South for causing the war. His friend Mr. Simmons stated that Levy believed “the war was brought on by secessionists not being willing to be governed by Republicans….” Levy kept up with the Union victories and prophetically declared “the war was on account of slavery and that they [southerners] would lose them in the end.”

In 1871, Congress passed an act to establish the Southern Claims Commission. Levy went through the lengthy process of filing a claim. He had to appear and make a sworn statement, as did others who witnessed Levy’s personal property taken by Union soldiers living off the land. In his testimony, he conveyed that he and his family were left with nothing to eat. He was advised to go to a mill in town for help. At the gristmill, Levy was given some meal. Upon arriving home, he learned Colonel Lamb wanted to see him. Lamb told Levy, “Old man they tore you up badly, but I think someday you will get paid for what you have lost. I said to him that would not suffice for the present that I and my wife and children were without nothing to eat or wear. He then opened a trunk and gave me a coat and a shirt. Said he was very sorry.” It is important to note that Levy and those who testified on his behalf, were sworn in and given a deposition by John Mirror, a special commissioner for the State of North Carolina. Even the claims commissioner noted how well-to-do Levy was for a “colored man.” Levy did own quite a bit of land and the list of provisions taken from him illustrates a good portion of food stores.

Levy testified to the Southern Claims Commissioner that, after the Union Army arrived in Fayetteville in March 1865, a “large force of General Sherman’s army camped near him for 2 or 3 days.” A partial list of Levy’s property taken by the Union Army included: four “grown” cattle, one large ox, two young cows, several horses, sows, “twenty chickens at 25 cents each,” 175 pounds of lard, 100 bushels of corn, 50 bushels of peas, 275 bushels of potatoes, 1,500 pounds of fodder, five blankets, and three bed quilts. The soldiers were “obliged” to take what they wanted. Levy was assured that the government would repay him “by & bye.”

Levy’s sons, Lewis Jr. and Robert, testified that they watched the soldiers carry off their food and personal possessions on pack mules and in government wagons. The Union camp was just a few miles away from their home and they testified that they went to the camp and saw the soldiers use what was taken. The commissioners who verified the testimony wrote that they had “no doubt” the soldiers “stripped him of all he had.”

Levy began his claim petition in the first half of 1872. It was October of that year before testimony was taken by the special commissioner, John Mirror. Levy requested $1,592.65. He received payment in 1877 in the amount of $723.

How many soldiers did Levy’s provisions feed? How far did the nourishment carry the Union troops, who after marching out of Fayetteville, went on to fight at Averasboro? Did the Levys, who were left with no food for themselves, recognize the sacrifice they made for the cause they supported? The sacrifices made by both Union soldiers and their supporters, like the Levys, resulted in freedom for the enslaved.

Lewis Levy’s legacy, in addition to being remembered for remaining loyal to the Union during the Civil War, resulted from the 37 acres of land he purchased in 1862 from J.J. Gilchrist for $40. Levy’s descendants built several homes on that property in the early 20th century. It was known locally as Levytown.

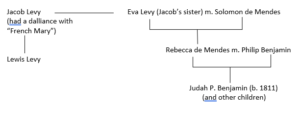

Side Note: Civil War enthusiasts might be interested in learning that Lewis Levy and Judah P. Benjamin were cousins. Judah P. Benjamin served as the Attorney General, Secretary of War, and Secretary of State for the Confederacy and attended Fayetteville Academy for a brief time, circa 1924-1925. See the attached diagram to see how Lewis Levy, a free person of color, was related to former Confederate cabinet member, Judah P. Benjamin.

Jacob Levy’s sister, Eva, gave birth to Rebecca, who married Philip Benjamin, and their oldest child was Judah P. Benjamin. Jacob Levy, Rebecca’s uncle, fathered Lewis Levy, making Lewis and Judah P. Benjamin cousins. It was Uncle Jacob who paid for Judah, and his brother and sister, to attend Fayetteville Academy.

Source: Levy, Lewis W record 16083 Southern Claims complete document.pdf