Written by Jeffrey W. Long (edited and vetted by Cheri Todd Molter)

Charles Wesley Cecil (1827-1911), my great-great-great grandfather, lived out a mostly ordinary life as a farmer and laborer in Davidson County, North Carolina. He was descended from a long line of Cecils who lived in Maryland, one branch of which had moved to Davidson County around 1800. Cecil family history records note that he went by the familiar name of “West,” but for the purposes of this narrative I will refer to him as “Wesley.” Wesley grew up on the farm of his father, Samuel Cecil, in the Arcadia community. After establishing his own family, he later moved to eastern Davidson County, just to the north of Thomasville. Like most common folk of the time, he and his wife, Elizabeth Holloway Cecil (1831-1912), had to work hard to support their family through some challenging times, including of course the Civil War and its aftermath.

While researching his life, I was not surprised to find Wesley listed among those who had served in the Confederate army. An initial examination of the records, available online through the National Parks Service, shows Charles W. Cecil on the roster of Company K of the 48th North Carolina Infantry, a regiment comprised of men from Davidson County and its neighboring counties. But Wesley’s Confederate service was more complicated than indicated by that simple listing. His story can be reconstructed with more details after additional research through Confederate service records, pension records, and newspaper accounts from the 1860s and from the time of Wesley’s passing in 1911.

One thing we know for sure from these records is that Wesley was not one of those men who rushed off to join the Confederate cause in that first year of the war. Yet, at age 35 in 1862, Wesley, a husband and father of two young children, found himself in the crosshairs of the Conscription Act, which was enacted in April of that year to address the critical need for troops in the Confederate army. Wesley received his conscription orders in August 1862, but as noted in his Confederate service records, he deserted from his company by August 15, 1862. Based on the information provided in census records, shortly before he was conscripted, Wesley and Elizabeth would have known that they were pregnant again, which may have influenced his decision to desert from the army. Their daughter, Ellen, was born in February 1863.

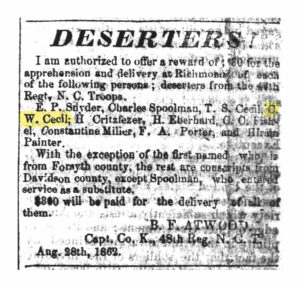

Wesley was not the only one from the area who did not wish to serve in the army: An article in the August 29, 1862 issue of the Western Sentinel, a newspaper based in Winston, states, “Deserters! I am authorized to offer a reward of $30 for the apprehension and delivery at Richmond of each of the following persons; deserters from the 48th Regt., N. C. Troops. E.P Snyder, Charles Spoolman, T. S. Cecil, C. W. Cecil, H. Critzfezer, H. Eberhard, C. C. Fishel, Constantine Miller, F. A. Porter, and Hiram Painter. With the exception of the first named, who is from Forsyth County, the rest are conscripts from Davidson County, except Spoolman, who entered service as a substitute. $300 will be paid for delivery of all of them. B.F. Atwood, Capt., Co. K, 48th Regt. N. C. T., August 28, 1862.” The “T. S. Cecil” noted here is Wesley’s younger brother, Thomas, who apparently was also hesitant to serve in the Confederate army.

Wesley was not the only one from the area who did not wish to serve in the army: An article in the August 29, 1862 issue of the Western Sentinel, a newspaper based in Winston, states, “Deserters! I am authorized to offer a reward of $30 for the apprehension and delivery at Richmond of each of the following persons; deserters from the 48th Regt., N. C. Troops. E.P Snyder, Charles Spoolman, T. S. Cecil, C. W. Cecil, H. Critzfezer, H. Eberhard, C. C. Fishel, Constantine Miller, F. A. Porter, and Hiram Painter. With the exception of the first named, who is from Forsyth County, the rest are conscripts from Davidson County, except Spoolman, who entered service as a substitute. $300 will be paid for delivery of all of them. B.F. Atwood, Capt., Co. K, 48th Regt. N. C. T., August 28, 1862.” The “T. S. Cecil” noted here is Wesley’s younger brother, Thomas, who apparently was also hesitant to serve in the Confederate army.

Wesley must have kept himself relatively well hidden from authorities, as his service record documents him as a “Deserter” as late as June 1863. But, sometime before Oct. 15, 1863, Wesley “returned” to serve with his unit. In January 1864, Wesley was hospitalized for dysentery. The next entry in his compiled military record states that he returned to serve with his company on May 17, 1864.

Whether from these hardships at the front lines, concern about his struggling family back home, or maybe political opposition to the cause of the war, Wesley seemed determined to make his army career short. Based on the information in his Confederate compiled record, on August 20, 1864, he was noted as “deserted to enemy,” and by Aug. 25th, he was “confined in Washington DC.” According to Union records, Wesley was a “Deserter from the Enemy” and “sent to Capt. Leslie, City Point (Virginia), [on] August 24, 1864.” His Confederate record stated that he took the Oath of Allegiance on Sept. 15, 1864. Wesley’s story of desertion was certainly not an uncommon one. While researching soldiers from Davidson County and its surrounding areas, one can find many men who behaved similarly, particularly in the final year of the war, as the armies of Lee and Grant battled it out in Virginia with horrific losses on both sides.

After the war, Wesley thankfully returned to his family in Davidson County and a much quieter existence. It appeared that he and Elizabeth may have fallen on tough economic times late in life and received some support from the county. Also, Wesley was noted in Cecil family records: “It is recalled by Thomas and Rebecca Eanes [she was Charles Wesley’s grand-niece] that Charles Wesley was a ‘teller of tall tales, and usually in a poor financial state. He would come over to Lexington from Thomasville to borrow a loan from more affluent members of his family.’”

In 1901, Wesley applied for a “Soldiers Pension” offered by the State of North Carolina. His application provides additional insights into his time in the Army. For example, Wesley was apparently wounded on multiple occasions during his military career, and they were verified by a doctor’s examination. He had been shot on the left side of his jaw and, as a result, had lost multiple teeth, and he had a bayonet wound in his left hand; both injuries were said to have occurred during the Wilderness Campaign of 1864. His pension was granted, and Elizabeth applied for a widow’s portion of the pension after Wesley’s death in 1911. I also found newspaper accounts that showed that Davidson County paid $20 toward Wesley’s funeral expenses, acknowledging him as “a Confederate Soldier.”

None of these later records take into account the somewhat questionable nature of Wesley’s commitment to the Confederate cause, and he certainly did not advertise that “lack of conviction” when it came to filling out his pension request (remember, he was a “teller of tall tales”). However, this was a time when collective memory of the Civil War experience was taking on a much more idealized nature, and Wesley’s story as a reluctant Confederate would not have been an unusual one for men from this part of North Carolina.

Sources:

“Compiled Service Records of Confederate Soldiers Who Served in Organizations from the State of North Carolina,” accessed via familysearch.org

“North Carolina, Confederate Soldiers and Widows Pension Applications, 1885-1953”; accessed via familysearch.org

National Parks Service Soldier Records: https://www.nps.gov/civilwar/search-soldiers.htm

Contemporary newspaper articles accessed via newspapers.com

1860, 1870, and 1900 U.S. Census Records

“300 Years of the Cecils” (see https://archive.org/details/300yearsofcecils00koch/page/48/mode/2up)

North Carolina Troops 1861-65, A Roster