Submitted by Amy Sinclair Dahm; Edited and vetted by Cheri Todd Molter and Kobe M. Brown

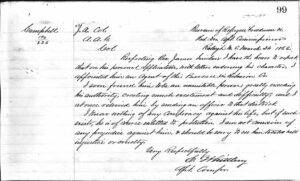

On January 29, 1866, less than a year after the war ended, Rev. James Sinclair spoke before a Congressional committee. Rev. Sinclair was a Scottish minister who had been living in North Carolina for some years and, in 1865, became an agent for Robeson County’s Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen, and Abandoned Lands. Although he had been an enslaver, Sinclair was a Unionist and had opposed succession. After the war, Rev. Sinclair worked to enforce Reconstruction laws and to help those who were newly emancipated, displaced, or dealing with other hardships. Rev. Sinclair is an example of one who would have been labeled a “scalawag”, a derogatory term used by southerners for a southern person who supported Northern Reconstruction efforts and nineteenth-century Republican ideas, and based on a Bureau ledger entry from March 1866, he had had to endure some societal pushback, possibly even death threats, because of his views. (See attached photograph of the March 1866 entry in a Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen, and Abandoned Lands’ Ledger from Raleigh, NC.)

INTERVIEW

REVEREND JAMES SINCLAIR, Washington, D.C., January 29, 1866

Question: What is generally the state of feeling among the white people of North Carolina towards the government of the United States?

Answer: That is a difficult question to answer, but I will answer it as far as my own knowledge goes. In my opinion, there is generally among the white people not much love for the government. Though they are willing, and I believe determined, to acquiesce in what is inevitable, yet so far as love and affection for the government is concerned, I do not believe that they have any of it at all, outside of their personal respect and regard for President Johnson.

Question: How do they feel towards the mass of the northern people—that is, the people of what were known formerly as the free States?

Answer: They feel in this way: that they have been ruined by them. You can imagine the feelings of a person towards one whom he regards as having ruined him. They regard the northern people as having destroyed their property or taken it from them and brought all the calamities of this war upon them.

Question: How do they feel in regard to what is called the right of secession?

Answer: They think that it was right … that there was no wrong in it. They are willing now to accept the decision of the question that has been made by the sword, but they are not by any means converted from their old opinion that they had a right to secede. It is true that there have always been Union men in our State, but not Union men without slavery, except perhaps among Quakers. Slavery was the central idea even of the Unionist. The only difference between them and the others upon that question was, that they desired to have that institution under the aegis of the Constitution and protected by it. The secessionists wanted to get away from the north altogether. When the secessionists precipitated our State into rebellion, the Unionists and secessionists went together, because the great object with both was the preservation of slavery by the preservation of State sovereignty. There was another class of Unionists who did not care anything at all about slavery, but they were driven by the other whites into the rebellion for the purpose of preserving slavery. The poor whites are to-day very much opposed to conferring upon the Negro the right of suffrage; as much so as the other classes of the whites. They believe it is the intention of government to give the Negro rights at their expense. They cannot see it in any other light than that as the Negro is elevated they must proportionately go down. While they are glad that slavery is done away with, they are as bitterly opposed to conferring the right of suffrage on the Negro as the most prominent secessionists; but it is for the reason I have stated, that they think rights conferred on the Negro must necessarily be taken from them, particularly the ballot, which was the only bulwark guarding their superiority to the Negro race.

Question: In your judgment, what proportion of the white people of North Carolina are really, and truly, and cordially attached to the government of the United States?

Answer: Very few, sir; very few.

Question: Judging from what you have observed of the feelings of the people of that State, what would be their course in case of a war between the United States and a foreign government?

Answer: I can only tell you what I have heard young men say there; perhaps it was mere bravado. I have heard them say that they wished to the Lord the United States would get into a war with France or England; they would know where they would be. I asked this question of some of them: If Robert E. Lee was restored to his old position in the army of the United States, and he should call on you to join him to fight for the United Sates and against a foreign enemy, what would you do? They replied, “Wherever old Bob would go we would go with him.”

Question: Have you heard such remarks since the war is over, as that they wished the United States would get into a war with England and France?

Answer: Oh, yes, sir; such remarks are very common. I have heard men say, “May my right hand wither and my tongue cleave to the roof of my mouth if I ever lift my arm in favor of the United States.”

Question: Did you ever hear such sentiments rebuked by bystanders?

Answer: No, sir; it would be very dangerous to do so.

Question: Is the Freedmen’s Bureau acceptable to the great mass of the white people in North Carolina?

Answer: No, sir; I do not think it is; I think the most of the whites wish the bureau to be taken away.

Question: Why do they wish that?

Answer: They think that they can manage the Negro for themselves: that they understand him better than northern men do. They say, “Let us understand what you want us to do with the Negro-what you desire of us; lay down your conditions for our re-admission into the Union, and then we will know what we have to do, and if you will do that we will enact laws for the government of these Negroes. They have lived among us, and they are all with us, and we can manage them better than you can.” They think it is interfering with the rights of the State for a bureau, the agent and representative of the federal government, to overslaugh the State entirely, and interfere with the regulations and administration of justice before their courts.

Question: Is there generally a willingness on the part of the whites to allow the freedmen to enjoy the right of acquiring land and personal property?

Answer: I think they are very willing to let them do that, for this reason; to get rid of some portion of the taxes imposed upon their property by the government. For instance, a white man will agree to sell a Negro some of his land on condition of his paying so much a year on it, promising to give him a deed of it when the whole payment is made, taking his note in the meantime. This relieves that much of the land from taxes to be paid by the white man. All I am afraid of is, that the Negro is too eager to go into this thing; that he will ruin himself, get himself into debt to the white man, and be forever bound to him for the debt and never get the land. I have often warned them to be careful what they did about these things.

Question: There is no repugnance on the part of the whites to the Negro owning land and personal property?

Answer: I think not.

Question: Have they any objection to the legal establishment of the domestic relations among the blacks, such as the relation of husband and wife, of parent and child, and the securing by law to the Negro the rights of those relations?

Answer: That is a matter of ridicule with the whites. They do not believe the Negroes will ever respect those relations more than the brutes. I suppose I have married more than two hundred couples of Negroes since the war, but the whites laugh at the very idea of the thing. Under the old laws a slave could not marry a free woman of color; it was made a penal offence in North Carolina for any one to perform such a marriage. But there was in my own family a slave who desired to marry a free woman of color, and I did what I conceived to be my duty, and married them, and I was presented to the grand jury for doing so, but the prosecuting attorney threw out the case and would not try it. In former times the officiating clergyman marrying slaves, could not use the usual formula: “Whom God has joined together let no man put asunder;” you could not say, “According to the ordinance of God I pronounce you man and wife; you are no longer two but one.” It was not legal for you to do so.

Question: What, in general, has been the treatment of the blacks by the whites since the close of hostilities?

Answer: It has not generally been of the kindest character, I must say that; I am compelled to say that.

Question: Are you aware of any instance of personal ill treatment towards the blacks by the whites?

Answer: Yes, sir.

Question: Give some instances that have occurred since the war.

Answer: [Sinclair describes the beating of a young woman across her buttocks in graphic detail.]

Question: What was the provocation, if any?

Answer: Something in regard to some work, which is generally the provocation.

Question: Was there no law in North Carolina at that time to punish such an outrage?

Answer: No, sir; only the regulations of the Freedmen’s Bureau; we took cognizance of the case. In old times that was quite allowable; it is what was called “paddling.”

Question: Did you deal with the master?

Answer: I immediately sent a letter to him to come to my office, but he did not come, and I have never seen him in regard to the matter since. I had no soldiers to enforce compliance, and I was obliged to let the matter drop.

Question: Have you any reason to suppose that such instances of cruelty are frequent in North Carolina at this time-instances of whipping and striking?

Answer: I think they are; it was only a few days before I left that a woman came there with her head all bandaged up, having been cut and bruised by her employer. They think nothing of striking them.

Question: And the Negro has practically no redress?

Answer: Only what he can get from the Freedmen’s Bureau.

Question: Can you say anything further in regard to the political condition of North Carolina—the feeling of the people towards the government of the United States?

Answer: I for one would not wish to be left there in the hands of those men; I could not live there just now. But perhaps my case is an isolated one from the position I was compelled to take in that State. I was persecuted, arrested, and they tried to get me into their service; they tried everything to accomplish their purpose, and of course I have rendered myself still more obnoxious by accepting an appointment under the Freedmen’s Bureau. As for myself I would not be allowed to remain there. I do not want to be handed over to these people. I know it is utterly impossible for any man who was not true to the Confederate States up to the last moment of the existence of the confederacy, to expect any favor of these people as the State is constituted at present.

Question: Suppose the military pressure of the government of the United States should be withdrawn from North Carolina, would northern men and true Unionists be safe in that State?

Answer: A northern man going there would perhaps present nothing obnoxious to the people of the State. But men who were born there, who have been true to the Union, and who have fought against the rebellion, are worse off than northern men. And Governor Holden will never get any place from the people of North Carolina, not even a constable’s place.

Question: Why not?

Answer: Because he identified himself with the Union movement all along after the first year of the rebellion. He has been a marked man; his printing office has been gutted, and his life has been threatened by the soldiers of the rebellion. He is killed there politically, and never will get anything from the people of North Carolina, as the right of suffrage exists there at present. I am afraid he would not get even the support of the Negro if they should be allowed to vote, because he did not stand right up for them as he should have done. In my opinion, he would have been a stronger man than ever if he had.

Question: Is it your opinion that the feelings of the great mass of the white people of North Carolina are unfriendly to the government of the United States?

Answer: Yes, sir, it is; they have no love for it. If you mean by loyalty, acquiescence in what has been accomplished, then they are all loyal; ff you mean, on the other hand, that love and affection which a child has for its parent even after he brings the rod of correction upon him, then they have not that feeling. It may come in the course of time.

Question: In your judgment, what effect has been produced by the liberality of the President in granting pardons and amnesties to rebels in that State—what effect upon the public mind?

Answer: On my oath I am bound to reply exactly as I believe; that is, that if President Johnson is ever a candidate for re-election he will be supported by the southern States, particularly by North Carolina; but that his liberality to them has drawn them one whit closer to the government than before, I do not believe. It has drawn them to President Johnson personally, and to the democratic party, I suppose.

Question: Has that clemency had any appreciable effect in recovering the real love and affection of that people for the government?

Answer: No, sir; not for the government, considered apart from the person of the Executive [that is, President Johnson].

Question: Has it had the contrary effect?

Answer: I am not prepared to answer that question, from the fact that they regard President Johnson as having done all this because he was a southern man, and not because he was an officer of the government.

Source:

Source containing the entire transcript from all three interviews https://www.stolaf.edu/people/fitz/COURSES/SouthernViews.htm